by Howard Fosdick © FolkFluteWorld.com.

Have you tried playing the bawu flute? How about the hulusi?

Both are unique flutes that hail from China's Yunnan province and adjacent areas. This is the ancestral home of the Dai and Yi peoples. Yunnan is one of the southernmost provinces in China, bordering Myanmar, Laos, and Vietnam. The province is home to nearly 50 million and its history stretches back to antiquity.

This comprehensive guide covers three flutes native to Yunnan and its near neighbors: the vertical bawu, the transverse bawu, and the hulusi. These instruments are quite similar in many respects, so this article applies to all three. Whichever of these three flutes you have, this article should prove useful.

Here's the outline:How They Sound

Three Related Instruments

Materials and Styles

Keys

Fingering

Hulusi Differences

Non-Standard Designs

How to Play

Alternative Fingerings and Sharps and Flats

How to Play with Style

How to Care for Your Flute

How to Fix Your Flute

Free Learning Resources

Purchasing Tips

Final Words

---Appendices---

Common Problems with Solutions

Complete Chromatic Scales

Translating Chinese to Western Notations

How to Read Chinese Musical Notation: Jian Pu

History of Bawus and Hulusis

How They Sound

Before we discuss these instruments, here are a couple audio clips to show how they sound. You can play them on background while you read this article.

Here is Bazi Mountain Song played in Chinese style on a bawu flute. And here is a Hulusi solo.

Three Related Instruments

The vertical bawu, transverse bawu, and hulusi are three closely-related free reed instruments. Here's how they look:

A Vertical Bawu, a Transverse Bawu, and a Hulusi (Photos courtesy of OrientalMusicSantuary.com and AllExpress.com)

You play the vertical bawu by extending it straight out from your mouth, like a clarinet or recorder. Since you put your mouth on one end of the instrument, some call this the end-blown bawu.

You play the transverse bawu by holding it sideways to your body, just like a metal concert flute. For this reason, some call it the sideways bawu or horizontal bawu.

You play the hulusi vertically, just like the vertical bawu. The hulusi is also called the gourd flute because of the calabash gourd shape near its mouthpiece. You may also see it referred to as the calabash flute or the cucurbit flute.

What distinguishes these three instruments from other flutes -- and makes them similar to one another -- is that they are all free reed instruments. That is, each has a reed, just like a clarinet or saxophone. A reed is a thin strip of vibrating material that produces a sound. The vibration is what creates the sound waves.

In a clarinet or saxophone, the reed is directly attached to the instrument's mouthpiece. The player thus places touches the reed with his tongue. Here's how a saxophone mouthpiece looks, for example:

A Saxophone Mouthpiece with Reed (Courtesy of Notestem.com)

With free reed instruments, the player does not directly touch the reed at all -- it vibrates freely, hence the term free reed.

The photo below shows a close up of a vertical bawu. The upper piece is the body of the instrument, while below it is the mouthpiece that attaches to the body. You can see the free reed inside the instrument's body, to the top right. That little rectangle encases the metal reed. Usually it's brass or a copper alloy.

The Mouthpiece and the Free Reed

When you reassemble the two parts of the instrument, that reed becomes hidden inside the mouthpiece.

You blow into the fipple on the left side of the picture (which is at the top of the instrument), and your air is forced through the free reed inside the mouthpiece. Its vibration is what creates the sound waves. These then travel down the body of the instrument. While the sound waves are in transit, you finger the holes along the body of the instrument to produce different pitches or notes.

Here's a close up of the free reed. You can see that it's a thin metal "V" connected at its base to the metal rectangle. That thin little triangle or "V" is what vibrates to create the sound waves.

The Free Reed

In the hulusi, the free reed is hidden from view, inside the instrument, just as with the vertical bawu. When you take apart a hulusi into its components, you can see how the central pipe contains a free reed:

Hulusi Components Disassembled (Courtesy of LMS Store at Amazon)

With the transverse bawu, you can see the free reed embedded underneath the mouthpiece. You can see the white mouthpiece in this photo, and inside it is the metal reed.

A Transverse Bawu, Its White Mouthpiece, and the Reed Inside (Courtesy of AllExpress.com)

The free reed is what gives the bawu and hulusi their unique sound. You recognize this sound immediately in the music to a film like Crouching Tiger, Hidden Dragon.

Given their common free reed technology, you play and maintain these three instruments in similar manner.

Materials and Styles

Bawus and hulusis can be made of any of several materials. Wood is most common, especially bamboo, black sandalwood, rosewood, and ebony. You might even run across one with metal, plastic, or ceramic components. In general, materials shape the sound of the instrument a bit, but probably less so than the pitch range and musician's skills.

Wood generally elicits a warmer, softer sound, while metal projects brightly. Plastic is very durable and inexpensive.

Bawus and hulusis traditionally come with an attachable tassle. These are strictly ornamental and do not affect either their sound or how you play them.

Some instruments feature intricate patterns or Chinese characters, while others come unadorned. Here's a hulusi with tassle, fancy decoration, and carrying case with characters:

Hulusi with Ornamentation (Courtesy of Ebay)

Sometimes people wonder if they can reach all the fingering holes on lower-pitched, large flutes. This is a concern, for example, with tenor recorders and low pitched penny whistles.

Don't worry about this with bawus and hulusis. Even the largest comfortably fit averaged-sized hands. For example, my low G bawu is 22" long. Yet the complete span between the first and last fingering holes is only 4.5 inches. Compare this to the typical 8 to 9 inch span of tenor recorders.

Keys

In the western musical tradition, the key of an instrument is identified by its lowest note. This is the note you play on a folk flute with all the fingering holes closed.

For example, close all the fingering holes on a common soprano recorder, blow a note, and it will voice a C. Thus we call it "a recorder in the key of C," or a "C soprano recorder."

The Chinese tradition differs. They name the key of a flute from the note produced when all three left hand fingerholes are closed, and all three right hand fingerholes are open.

What this means is that if you buy a bawu or hulusi in the key of G, for example, in western terminology, it's actually a flute in the key of D. Its lowest or fundamental note in western terms would be D.

This chart shows how Chinese keys map onto western keys:

Bawus and hulusis can be purchased in nearly any key.

Bawus are most commonly tuned to the Chinese keys of G or F. (In western terms, these would be the keys of D and C, respectively.) Hulusis are most commonly pitched in the higher keys of C or B♭ (G or F in western terminology).

It's helpful to know these equivalences so that you can map any knowledge you may have of western music to the Asian traditions.

Going forward, I'll use the Chinese terminology as this is what you'll normally run across for these instruments.

Fingering

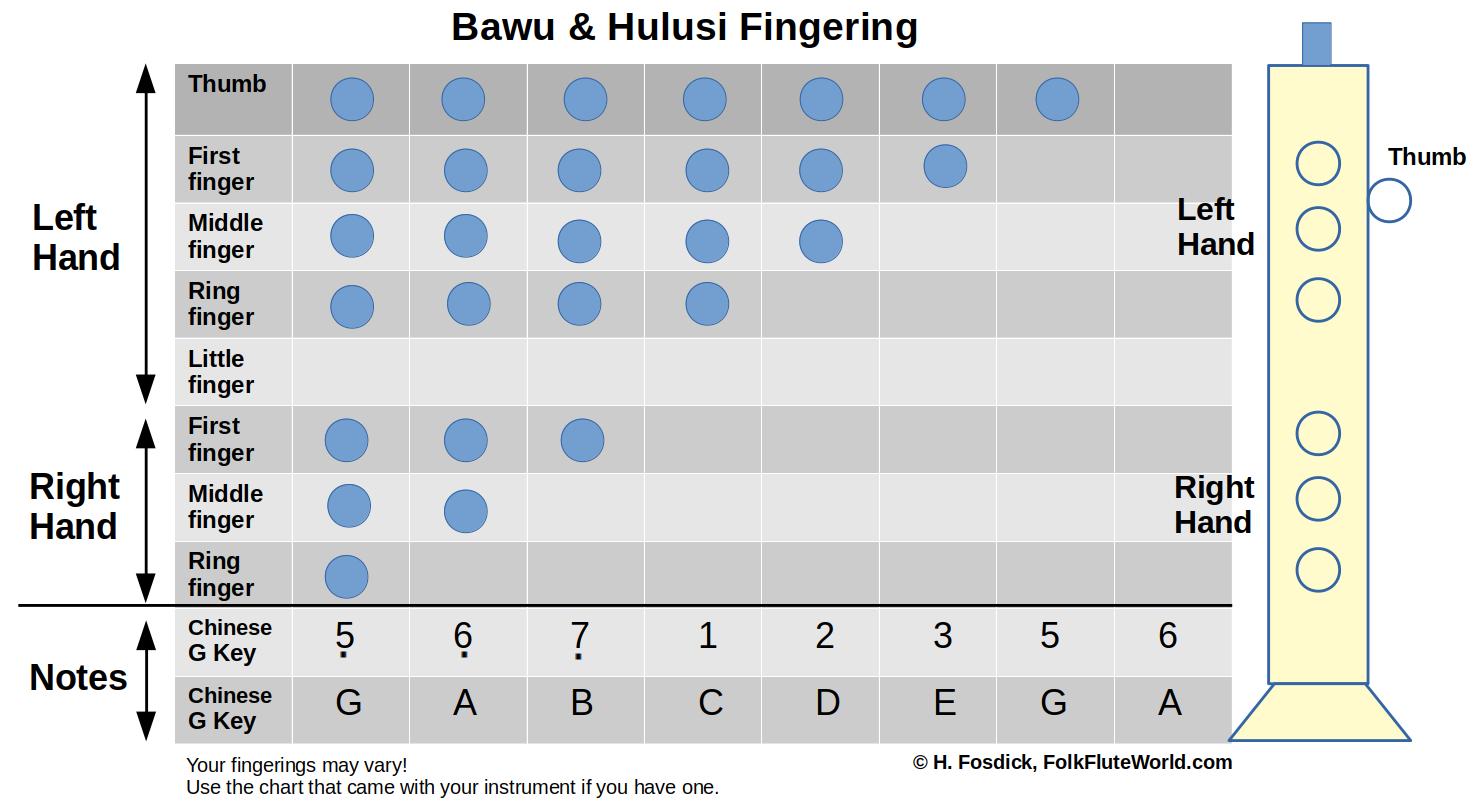

Fingerings for Bawus and hulusis are not always standardized. So if yours came with a fingering chart, you should use that chart.

However, many instruments ship without documentation. Or their documentation is in Chinese. So here is a chart that shows the basic fingering common to nearly all instruments.

The diagram on the right side of the figure shows how you position your hands on a vertical bawu, or on the center tube of the hulusi.

For the horizontal bawu, just rotate the instrument 90 degrees in your imagination so that it's horizontal instead of vertical, with the mouthpiece positioned to the left side. Then finger your flute in the exact same way. Your right hand rests on the instrument furthest away from your mouth.

The fingering chart shows that to climb the scale, from lowest note to highest, first you cover all fingering holes. Then, you simply progressively remove your fingers, one at a time, from the bottom of the instrument up to the top. Pretty easy, right?

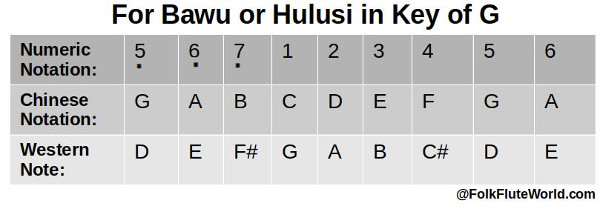

The last two lines of the chart show the notes each fingering will voice for a bawu or hulusi in the Chinese key of G. I've included these two lines because this is similar to what you'll typically see on a Chinese fingering chart.

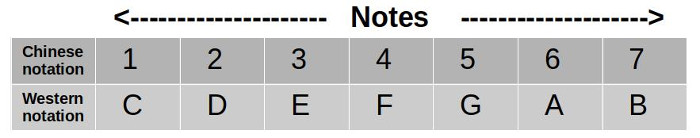

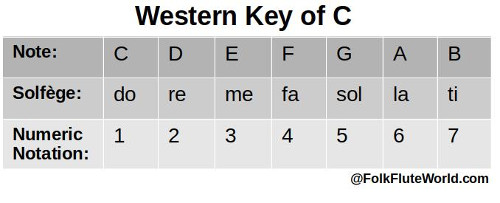

Take a closer look at the second line from the bottom in the chart. This contains the common Chinese notation for notes. This numbered musical notation maps like this to western scales:

Chinese vs Western Musical Notation (By FolkFluteWorld.com)

Thus, "1" in Chinese notation is the note of "C", "2" is the note of "D", and so on. It's pretty simple.

A dot below any note indicates a lower octave, while a dot above a note means a higher octave. You can see that the fingering chart uses that convention to show that the first three notes are in a lower octave.

It's useful to understand this simple mapping because you'll often see this Chinese notation if you read about bawus and hulusis.

Hulusi Differences

We've seen that the hulusi fingers the exact same way as the bawu. You just finger the center or main tube of the hulusi.

The way that hulusis differ from bawus is in their drone pipes. Most hulusis have two shorter tubes, one to to each side of the main one. These are its drone pipes. Each sounds just a single note while you finger the central tube.

Hulusi drone tubes have a stopper or switch of some sort to determine whether they sound. Open the muffler, and you finger the melody on the central tube while the drone(s) play a single sustained note. Close the drone tubes, and you have a one-note-at-a-time melody instrument. Just like a bawu. So, you can view a hulusi as just a bawu with drone pipes, and a gourd on top.

Non-Standard Designs

Before continuing, we should mention that bawus and hulusis are not always standardized. For example, a few bawus are double-tubed, like the one below. You blow into the hole for the tube you want to play.

A Double Transverse Bawu (Courtesy: Amazon)

And, there are hulusis that have different numbers of drone pipes. What we address in this article are the most common configurations: a single-pipe bawu (either vertical or horizontal), and the hulusi with two drone pipes.

Some bawus and hulusis have seven or even eight finger holes on top, instead of the standard six. Seven holes yields a range that is one note longer, while eight holes provides two more notes you can play.

Other bawus and hulusis may have a double hole in place of one or two of the standard fingering holes. A double hole makes it easier to play certain sharps or flats.

A few bawus and hulusis have keys. These address the limited range of traditional instruments by expanding the range up to two octaves with a full set of sharps and flats. They're specialty items that need their own fingering chart. It will be interesting to see if these more capable bawus and hulusis expand into general use in the future. For now, they're non-standardized, expensive, and rather rare, so we'll leave them out of this discussion.

How to Play

If you're learning the hulusi, switch off the drone pipes while you learn the basics of the instrument. You can switch them back on once you gain basic expertise.

If you're learning to play the horizontal bawu, understand that playing it is fundamentally different than playing transverse flutes that do not use a free reed. With the metal concert flute, for example, your goal is to rest your lower lip on the lip plate, then split your breath on the opposite side of the blow hole. This not how to play the bawu. With the bawu, you put your entire mouth onto the mouthpiece and blow. Do not touch the free reed with your tongue.

Okay. There are two fundamental requirements to playing bawu or hulusi. First is fingering. Use the fingering chart that came with your instrument. If you have none, use the chart above.

The second part of playing the bawu and hulusi is how hard you blow. Proper breath pressure is essential. This breath pressure varies by the note you are trying to play.

So let's play a couple notes. Cover all fingering holes and the thumb hole, then blow. Then lift up your farthest out righthand finger and blow again.

If all went well, you played the lowest note of the instrument, then you played one note higher.

If both notes sounded the same, you aren't blowing hard enough. Try again with more wind. If you're used to playing the recorder or similar flutes, you'll find that the low notes on the free reed instruments require much stronger breath pressure.

Did you get the two lowest notes this time?

If the notes didn't sound stable and true, you probably aren't thoroughly covering each hole. You must be sure that when you intend to cover a fingering hole, you completely cover the hole. You can't let any air escape from a hole you think you're covering! Otherwise the note will not sound properly. Use the pads of your fingers, rather than your fingertips, to ensure you fully cover holes.

Once you've played your first few notes, your goal should be to learn how to play all the notes in the basic scale. Play up and down the scale until you feel comfortable with it. It might be difficult at first to cover every hole accurately, but with practice you'll develop "muscle memory" and you'll find it easy to navigate the scale.

Try to play an individual note and see if you can hit it accurately. Again, if you've never played an instrument, this make take some practice, but quite soon it will become trivial to you.

You may experience some difficulty playing the highest couple notes. This is because they require much less breath pressure than that needed for lower notes. Try to attain the high notes by providing very low breath pressure.

What you're learning is that playing a specific note means fingering it properly and blowing with the correct pressure for that note.

Remember this rule:

Proper fingering + proper breath pressure = correct note

In general, you need more breath pressure on the lower notes and less on the higher ones. So you decrease your breath pressure as you climb the scale. You may need a pretty delicate breath to sound the two highest notes.

Be sure to keep your breath pressure even for the entirety of each note. Sometimes beginners will begin a note with insufficient pressure and not hit the note truly from the start. Or maybe they don't cleanly terminate a note, leading to a "honk" or a brief squawk as they quit the note. Try to articulate each note accurately from start to finish with proper breath pressure. You should hear one note and only one note if you're articulating a note correctly.

Once you've become comfortable in playing all notes in the simple scale, you should be able to play simple songs. Now, you're ready to move on to more advanced fingerings ...

Alternative Fingerings and Sharps and Flats

On many instruments you can play an extra note below those in the basic fingering chart. You do this by playing your instrument's lowest note (all holes closed) while underblowing the note. By underblowing, we mean that you play the note with very low breath pressure. You'll probably be able to produce a sound two notes lower than your all-holes-closed note.

For example, on a G bawu, your lowest note in the Chinese notation is G. Cover all the holes and blow very softly, and you might be able to voice an E below that G.

On some instruments you can even underblow the second lowest note. This often voices one note lower. So you could underblow a A to produce a G, for example.

Try this out to see if underblowing works for you. It usually works on the lowest note or two but not for higher notes. Instruments do vary.

Part of the learning process is experimenting with different fingerings and breath pressures to see what your instrument can do. For example, the fingering chart above excludes sharps and flats for clarity. That's because bawus and hulusis are usually considered diatonic, meaning that they play whole notes but not sharps or flats.

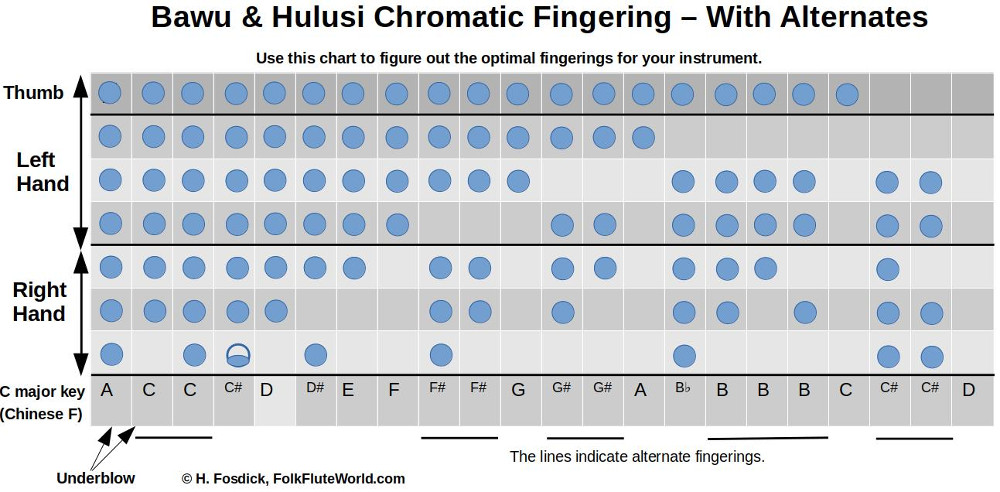

However, you can in fact play semitones on most instruments. The complete chromatic fingering charts at the end of this article shows how to finger them.

Instruments vary a good bit when it comes to the semitones. That's why the chromatic chart shows alternative fingerings for several of the notes. You'll have to experiment to see which work best on your instrument.

If you don't have a full fingering chart, it might be useful to print our chromatic chart. Then mark over it with the fingerings that work best for you as you discover them. That way you can keep track of them as you learn.

Some people half hole to play certain sharps and flats. That means covering half of a hole with your fingertip. You'll notice in the chromatic fingering chart that there is really only a single note that requires half-holing (the sharp of the instrument's lowest note.) Thus, half-holing is an advanced technique that's not really necessary for any but the most advanced players.

Finally, you might also experiment with inhaling to play notes (instead of the normal exhaling). Just like the harmonica -- another free reed instrument -- you can inhale to produce a note. With the bawu and hulusi, I've found inhaling a note useful only on rare occasions with the lowest notes. It rarely works with the higher notes. It's not like a harmonica where inhaling produces a whole new range of useful notes.

How to Play with Style

One of the distinguishing advantages of free reed instruments is their stylistic capabilities. Flute players refer to these as stylistic devices or ornamentation. You'll hear skilled musicians employ them often. In fact, they're a prominent part of Chinese bawu and hulusi music. You'll definitely want to learn these techniques if you wish to play Asian songs authentically.

This brief audio clip demonstrates many of these ornamental flourishes.

Here are a few common techniques you'll want to explore:

Tonal Quality: Experiment with your embouchure, or the way you place your mouth on the fipple. Free reed instruments are less sensitive to embouchure than some other kinds of flutes, nevertheless, optimal emboucher for each note enhances your playing.

Breath Control: We've already mentioned how breath control helps determine accurate pitch. Another aspect of this skill is phraseology, the ability to breathe at optimal points in a composition. You want to learn to time your breathing so that it does not disturb the natural grouping of notes into musical phrases. This leads to the dramatic expressiveness that enhances any performance.

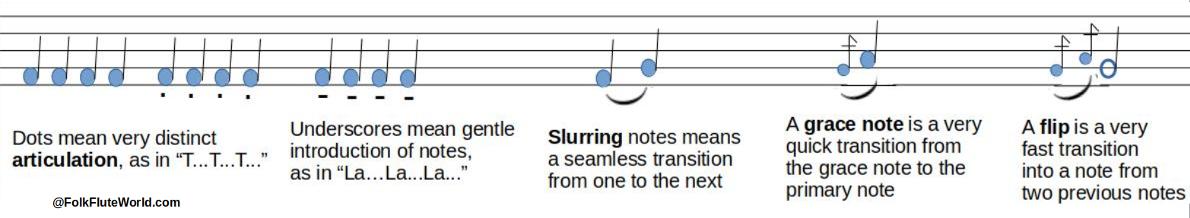

Articulation: You can start, connect, and separate notes in different fashions. One aspect of this is attack, the way you initiate a note. You can begin it softly or stealthily with an "L" sound, or more sharply with a "Th" or "D" sound. Use a "T" for the sharpest attack. Another technique: you can transition between notes very distinctly, or you can connect them by slurring them together.

Musical Techniques

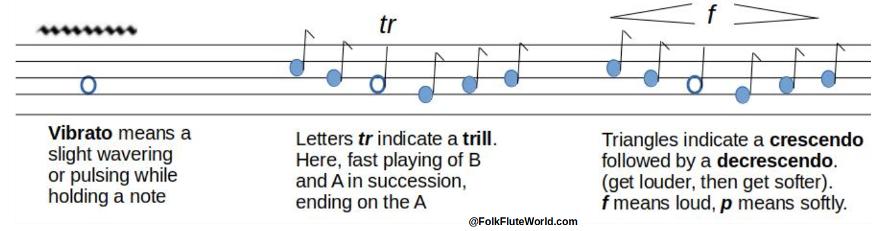

Grace Notes and Flips: A grace note is a very quick lead-in to a primary note. A flip is where you start on one note, flip to an adjacent note, and then go back to the primary note. The whole process is very rapid. Musical notation indicates grace notes and flips by placing smaller-sized notes prior to the primary note.

Vibrato: Vibrato refers to the very slight wavering or pulsing you hear when a musician holds a note. All flute players know this to be a key element when playing solos. With free reed instruments, you can obtain vibrato in either of two ways. First, you can shake or wave your finger lightly upon a hole. Second, you can achieve breath vibrato, where you very slightly increase and decrease your breath as you hold a note. Youtube videos can help you learn breath vibrato. The technique is the same regardless of the type of flute you're playing.

More Musical Techniques

Trills: A trill is a rapid fluctuation between two adjacent notes in the scale. For example, you can trill quickly between B and A in by quickly lifting up and putting down the finger that distinguishes between the two notes. Rapid tonguing and flutter effects are another aspect of what westerners often consider trills, but they're unique effects in their own rights.

Dynamics: Dynamics refers to the loudness or softness with which you play a note or a musical phrase. I've found free reed flutes a bit less versatile for dynamics than other instruments simply because certain breath pressures are required to play notes accurately and in tune. Nevertheless, you can achieve good dynamics with practice.

In musical notation, two diverging lines above or below the staff indicate crescendo, or increasing loudness, while two converging lines refer to descrescendo, or descreasing loudness. The above figure illustrates. You might also see the letter f used for a loud note or passage, and p for a soft one.

Slides or Glissando: This refers to transitioning seaminglessly between two adjacent notes. In other words, you slide from one note to the next. You can learn glissando with a bit of practice on how you move from one note to the next while properly controlling your breath pressure.

Note bending: This is where you vary the pitch of a note away from its starting point while you sustain the note. Sometimes you exit the note on its new pitch. Othertimes, you bend it back to its starting point before ending the note.

How to Care for Your Flute

Bawus usually come in two pieces: a head and a body. Just remove the head from the body to clean the instrument. The central pipe of a hulusi is just like a bawu: it removes from the gourd. The drone pipes are also removable for maintenance.

Wood instruments call for some careful handling if they are to remain playable. You'll notice that moisture builds pretty quickly within the flute. Just take the pieces of the instrument apart, then swab them with a gentle cloth.

The reed is especially delicate. Moisture affects it quickly, but you must be very careful not to disturb it if you touch it with any cloth to dry it. We suggest naturally airing out the reed so as not to disturb it.

Always make sure a wood instrument is at room temperature before play. Letting it sit in direct, hot sunlight, or bringing it in from outside in winter then immediately playing it in a warm room could harm the instrument.

Some musicians like to oil their wood flutes, exactly as one might a wood recorder. Sweet canola oil or sweet almond oil (with vitamin E added to prevent rancidity) are the usual choices. You might look into what specific oil is recommended for your kind of wood.

Be sure to use your case to protect your instrument, especially when you travel. That's its purpose!

How to Fix Your Flute

You definitely want to know how to repair your free reed instrument.

If you buy an inexpensive instrument, you could find that it plays poorly. Or you might have a nicely working flute that becomes unplayable over time.

You might find that one note "buzzes" when you play it. Or, that the highest or lowest notes don't play well, or at all.

In all cases, the most likely culprit is the reed. The free reed is quite delicate. It must be precisely positioned to play correctly. If it gets bent out of shape only slightly, it may not play well.

Here's a typical reed in optimal playable position:

Close up of the Reed

You can see that the tip of the reed (the end of the "V") is raised ever so slightly above the surrounding framework. This is its optimal position.

Before we proceed, a warning. The reed in your instrument is very delicate. Unless you feel you can safely make minute adjustments to it, you should look for a qualified individual to do this for you!

Okay. Sometimes breath pressure will cause the reed to bend a bit. For example, over time it might start to pull away from the framework. In this case, just adjust the reed ever so slightly to move it back to be more level with the surrounding frame. Be careful not to depress the reed below the framework.

For example, if the lower notes play well but the upper notes do not, you may need to raise the end of the reed a tiny bit. Slip something under the reed to raise it a tinsy bit.

Conversely, if the higher notes sound nicely but the lower notes razz or don't sound cleanly, lower the reed a tiny bit. You can do this simply by depressing it very gently with your finger. Careful! Do it incrementally with very gentle pressure.

If a note buzzes, this may mean that the reed is not separated enough from the surrounding framework. In this case, take a very fine penknife and articulate around the vibrating portion of the reed (around the "V"). This teeny bit of separation will eliminate the buzzing. I've found that this adjustment can improve an inexpensive instrument that isn't carefully quality-checked before it's shipped.

Another problem: what do you do if your instrument develops a crack somewhere in its body? As we mentioned before, prevention is the best approach. Don't subject the flute to extreme temperatures or sudden temperature variations.

If your instrument has already cracked, you can carefully apply a tiny amount of high quality superglue (cyanoacrylate) to flush the crack. This useful trick restores bamboo flutes to full functionality.

Free Learning Resources

Beyond your flute, you shouldn't have to buy anything to learn how to play and enjoy it. Here are a few free resources on the web:

- Find tons of free sheet music of all kinds here.

- Especially pertinent are these Chinese folk songs and these Japanese folk songs.

- Click here for bawu and hulusi Youtube videos with tips, advice and inspiring performances.

- Find several more fingering charts here.

There's not much online community for bawu and hulusi but there are a few options. The Traditional Chinese Music Forum occasionally has relevant posts. You might also check for relevant Facebook groups.

Purchasing Tips

Where should you purchase your bawu or hulusi? How can you be sure you're getting a good one?

First off, we recommend buying a quality instrument when you start. Otherwise, if the instrument has a problem playing some notes, you won't know whether it's your fault or the instrument's.

At the time of writing, a "good" instrument costs $50 or more. I wouldn't recommend at $25 instrument from Amazon or Walmart.

Secondly, if at all possible, you want to hear how the instrument sounds before you buy it. Does it play all notes in tune? Do you like its tone?

If you can, try the instrument out in person. Or if you buy online, be certain to hear a sound sample before you buy. If it's simply not possible to hear a sound sample beforehand, make sure you read the return policies in case you get sent an inferior or defective instrument.

Here are a few shops that sell bawus and hulusis. I recommend the first three because they specialize in Chinese instruments:

Eason Music Instruments Store -- Singapore

Sound of Mountain Music -- China

Amazon -- US and other countries

Walmart -- USA

Interact China -- China

China Market Advisor -- China

Final Words

I hope you've found this article helpful. If you have any comments or recommendations for improvement, please contact me via my contact information.

Meanwhile, I hope you'll explore the extra material that follows.

Complete Chromatic Scales

Translating Chinese to Western Notations

How to Read Chinese Musical Notation: Jian Pu

History of Bawus and Hulusis

--- Common Problems with Solutions---

Help! My flute came without any instructions. That's why I wrote this article. Read it and use our fingering chart and you should be able to figure out everything just fine.

I used your fingering chart but one note sounds sharp or flat. Remember that these are folk flutes and may not always be standardized. If a fingering chart came with your instrument, use it instead of ours. Our chart may not apply to your instrument for certain notes.

You may have to experiment to determine proper fingering for all the notes of your instrument. We offer our full chromatic chart to assist you in this.

I blow and finger the instrument, but the notes don't change. You are not blowing hard enough. Blow harder. Experiment with your breath pressure to correct this.

I can't sound the highest note or two. You are blowing too hard on those notes. Blow very lightly to attain the highest note. Experiment with your breath pressure to correct this.

My lowest note (played with all finger holes closed) sounds off-key. This is an issue with some instruments. First, make sure your breath pressure is appropriate for the note. Experiment using different pressures to see if this fixes the problem. If not, try underblowing (very softly blowing) each of the bottom two notes. Often one of these will sound an accurate pitch as an alternative for the note you're supposed to be able to play with all holes closed.

I play for a while then the instrument stops working properly. Too much moisture may have accumulated in the instrument. Open it up and dry it out. Check the reed, there's probably droplets there affecting the sound. Be very careful not to disturb the reed when you dry it! (It may be best to let the moisture evaporate naturally by giving the instrument a rest.)

One or two notes make a buzzing sound when I play them. The reed may not be cleanly or sufficiently detached from its surrounding frame. Follow the procedures we explain above for fixing the reed.

My flute is warping or cracking. Prevention works best. Follow the procedures we explain above for properly maintaining a wood instrument. Do not leave the flute in direct sunlight or where it could heat up too much. Don't leave it outside in the cold. Always bring the flute to room temperature before playing it. Make you sure remove any accumulated moisture in the instrument when you are done playing. In a long session, check the moisture level during play.

If your instrument has already cracked, you can carefully apply a tiny amount of high quality superglue (cyanoacrylate) to flush the crack. This useful trick restores bamboo flutes to full functionality.

How do I play sharps and flats? Bawus and hulusis are typically considered diatonic, meaning that they play whole notes but not sharps and flats. However, with a little experimentation you can usually figure out how to play most of the accidentals. I provide a fingering chart for how to play sharps and flats below.

--- Complete Chromatic Scales ---

If a fingering chart came with your instrument, you should use it. If not, I've provided a full chromatic scale below.

The purpose of this chart is to show you the common alternate fingerings for certain notes. These helps you figure out the optimal fingering for your own instrument.

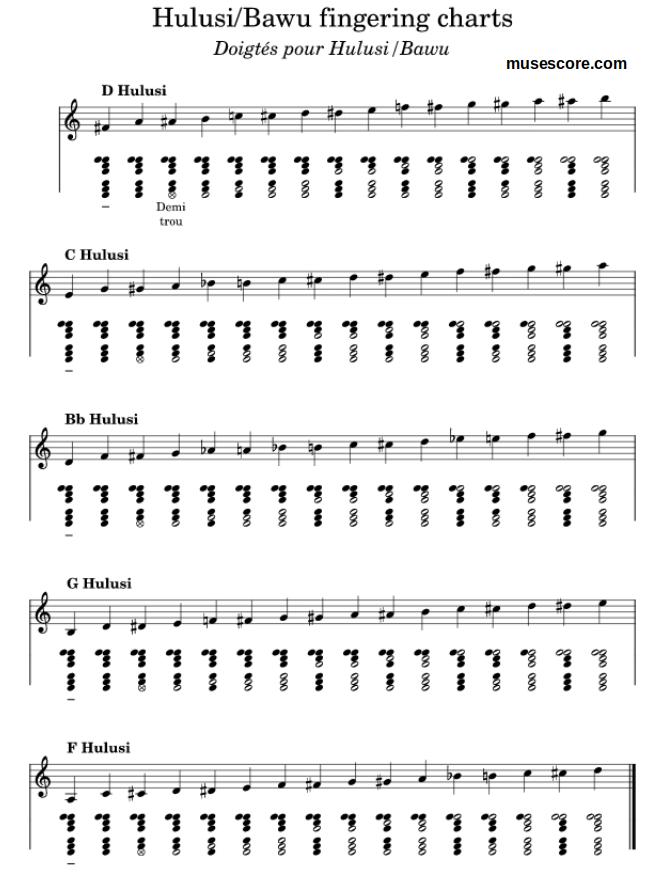

This next chart maps between the Chinese keys of bawus and hulusis and their equivalent staff notations in western music:

(Chart courtesy of Bork77 at Musescore.com)

--- Translating Chinese to Western Notations ---

We've already mentioned that Chinese and western keys differ. In addition, China and other Asian nations use a numbered numerical representation for individual notes.

This figure shows how the Asian numerical notation maps to European or western notations:

Here's how this applies to a bawu or hulusi in the Chinese key of G, as you'll see it in Chinese fingering charts:

The first row shows the numeric notation you'll see on a Chinese fingering chart for a bawu or hulusi in the key of G. The dots below the numbers indicate a lower octave. (Dots above represent a higher octave.)

The second line shows the equivalent notes.

The third line shows the notes that sound from the instrument, based on standard western musical notation.

Thus a bawu or hulusi in the Chinese key of G is actually in the western key of D. The third line shows how these notes sound in western notation, in the western key of D.

--- Reading Chinese Musical Notation: Jian Pu ---

The discussion in the previous section leads us right into how to read Asian sheet music. This can be very useful because you'll often encounter such notation on the internet if you want to play authentic Asian songs.

These songs are often written in a notation called Jian Pu (also translated as jianpu). Let's complete our explanation so that you can read Chinese music.

Pitch: Pitch maps to western notes as described above. A song typically will have an indication of its key at the top. This tells you how the above mapping works. For example, a declaration like "1=C" tells you that the key of the scale is C, so the mapping will be:

1 2 3 4 5 6 7

C D E F G A B

On the other hand, a statement like "1=G" changes the base note of the mapping like this:

1 2 3 4 5 6 7

G A B C D E F

Sharps and Flats: These are indicated by "#" and "/". For example, an F# would be written as #4. B♭ would typically show as 7/. But it's not uncommon to see the western symbols "#" and "♭" placed before the notes. (Interestingly, the Chinese bawu and hulusi fingering charts I've seen usually leave out any indication of sharps or flats.)

Note Length: A plain, unadorned number is a quarter note. This is the basic timing unit.

Each underline beneath a note halves its length. Thus, a note with no underline is a quarter note, a note with a single underline is a eighth note, and one with two underlines is a sixteenth note.

Each dash that follows a note lengthens it by one quarter note.

A dot after a note lengthens it by half, the same as in western notation.

The number "0" represents a musical rest, a silent interval in which you don't play any note. A plain "0" is a quarter note rest. The same rules for lengthening or shortening notes applies to rests. However, it's common to see rests extended merely by repeating "0"s, such as: 0 0 0 0

Okay. Those are the basic rules. You can find much more detail in the Wikipedia article on jian pu.

Here's an example song that shows the correspondence between jian pu and western musical notations. If you study it for a few mintues, it will make all this much more clear:

(Courtesy of Lists.GNU.org)

--- History ---

Some readers might be interested more detailed historical background on Chinese free reed instruments.

China has a rich fluting tradition. The country has evolved some two dozen different kinds of flutes. Among them are the dizi, xiao, sheng, and of course the bawu and hulusi. Some Chinese flutes are edge-blown, while others include a fipple or air duct to direct the musician's wind to the proper location to produce sound. The bawu and hulusi are members of this latter group.

Chinese flutes include both vertically- and horizontally- played forms. Probably for this reason, the bawu comes in both formats.

Over the years, the bawu and hulusi were increasingly adopted across China. And since the turn of the century, musicians outside China have turned to these instruments as well. This includes many European and Latin American composers. The unique voice of free reed flutes secures them a special place among the many different kinds of flutes.

An example of how free reed instruments have spread beyond Asia is in the film, Crouching Tiger, Hidden Dragon. That movie's soundtrack relies extensively on the bawu. It lends the film a sense of mystery and otherworldliness to those unfamiliar with the sound of these instruments.

OriginsThe bawu flute likely originated in China's Yunnan province (formerly called Hunan). This is a province of some 50 million people. Several ethnic groups play the bawu including the Dai, Yi, Hani, Miao (Hmong), and others. While likely originating among Chinese ethnic groups, the instrument spread regionally to parts of Vietnam, Myanmar's Shan state (Burma), India's Assam state, and Laos.

The story is the same with the hulusi. Originally favored by the Dai, De'ang, Achang, and Wa peoples, it's spread much more widely in modern times. Today, you can see indigenous bawus and hulusis in places as diverse as Thailand, Bangladesh, Taiwan, and Cambodia.

No one really knows when bawus and hulusis first evolved, but some sources claim lineage all the way back to the Qin dynasty (221 to 206 BCE).

What is known is a mythological origin story associated with these instruments:

It's likely that the bawu and hulusi were originally made from bamboo. This is the default choice for ethnic Chinese flute makers. With the spread of these instruments throughout China, today they're made from many different woods, as well as plastic, metal, and ceramic.

Obviously the hulusi owes its origins, in part, to the calabash bottle gourd that forms its neck. Non-Chinese will be interested to know that various kinds of squash and gourds form a primary staple in many parts of rural China, just as rice, corn, and wheat are fundamental staples elsewhere in the world.

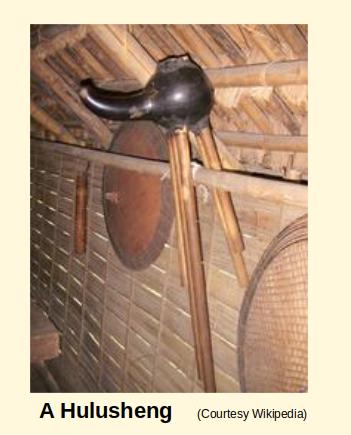

So the use of a gourd in a musical role may not be as odd as it might seem to some westerners. In fact, the hulusheng or gourd mouth organ also employs gourds in musical roles. This photo shows a gourd mouth organ used by the Ede people of Vietnam's central highlands.

What does the future hold for free reed flutes? Already we've mentioned that musicians and composers worldwide increasingly adopt them. In the United States, for example, you no longer have to search overseas to buy a bawu or hulusi. Amazon, Walmart, Ebay, Etsy and others will bring them right to your door.

In China, innovation and evolution continue. Today there are keyed bawus and hulusis that break from their traditionally narrow pitch range to a fully chromatic two octaves. It will be fascinating to see if these advanced forms of the instruments standardize and follow their predecessors to spread across the globe.

---------------------------

HOME

Like this article? Tell others at Slashdot, Digg, Reddit, or post on your favorite social media. Thanks!